Why the CNIL was powerless against Facebook (and why this will change)

Students who begin studying personal data law regularly ask this question: why does the CNIL sanction “digital giants” so rarely? The explanations they imagine are diverse and range from cowardice to laziness and lack of means.

None of these hypotheses is the right one. If the lack of means devolved to the CNIL is indeed an absolute scandal, so central has become the role of this authority in protecting citizens in the digital age, it does not explain the low number of convictions of “GAFA”. These companies, one can imagine, would be prime targets for controls, and possibly sanctions, if there were no other obstacles. The impoverishment of the CNIL, on the other hand, obviously prevents it from effectively controlling tens of thousands of more ordinary data controllers, such as SMEs or local authorities.

Dublin can be heaven

If the largest digital companies escape the control of the CNIL, it is because of a mechanism provided for in Article 56 of the GDPR and commonly referred to as “one-stop-shop”. The initial idea is rather appealing: if a data processing operation is “cross-border”, if it concerns several countries of the Union, then several national supervisory authorities have the vocation to work together on the file. It therefore seemed wise to designate a “lead authority” to coordinate their action. This authority will be that of the country where the “principal establishment” of the controller is located.

However, the major digital companies are often based in Ireland (Facebook, Microsoft, etc.) or Luxembourg (Amazon), countries that have long been distinguished by an appealing tax policy. In recent years, we have discovered that their sense of hospitality is also reflected in a healthy slowness in the implementation of the GDR.

he Dubhlinn Gardens with Dublin Castle in the background, Dublin, Ireland, J.-H. Janßen, CC-BY-SA.

Thus the association None of Your Business, founded by Max Shrems, may be on the verge of obtaining a decision against Facebook from the Irish Data Protection Commissionner (DPC), in the Europe – USA data flow case, after a legal battle that has been going on for almost 8 years.

The CNIL had certainly made its mark with a decision in January 2019 pronouncing a 50 million euro sanction against Google, the most important ever pronounced by the French authority on the basis of the DPC, but it was only a flash in the pan.

In a commentary on this decision, I explained that Google had not been less virtuous than other giants in Silicon Valley, but less skillful: it had been slow to clearly establish its European center for data processing decisions in the city of Dublin. The CNIL jumped at the opportunity to affirm: if there is no clear main establishment in a country of the Union, all national authorities are free to act independently of each other, as mavericks. This interpretation of the GDPR had not convinced all commentators, but the Conseil d’Etat found nothing to complain about. Since then, Google has taken due care to take proper refuge in Irish soil. All the Californian cats being perched, the CNIL had only to turn in circles while waiting for a postcard from its Dublin counterpart.

The one-stop shop is thus a machine to blow up the GDPR. Its implementation is a disaster. The European Commission has understood this: its famous Digital Services Act draft regulation provides for a one-stop-shop mechanism, but tempers it by giving the Commission the power to initiate proceedings itself if necessary (Article 51).

It should be emphasized, however, that Luxembourg and Irish procrastination, whether deliberate or not, cannot forever defer decisions on sanctions. The leading authority sets its tempo to the case, and it may opt for the march of the Foreign Legion rather than a quadrille. But the time for the decision must inevitably come. If, at that point, the proposed sanction is too lenient, it is Article 65 of the GDPR that comes into play. This gives the European CNILs, meeting within the framework of the European Data Protection Board, the capacity to put the leader in a minority after a vote. This is what happened recently to the detriment of the Irish authority, within the framework of a sanction inflicted on Twitter: the decision pronounced is not the one that was initially wanted by Dublin.

All the same, the DPC appeared to be the master of the clocks. Faced with the “GAFA”, one could believe that the French authority had become a paper tiger for months or even years.

Misfortune cookies

And then, in December 2020, a 100 million euro sanction was pronounced by the French authority against the Google companies (Google Ireland and Google LLC), and a 35 million euro sanction against Amazon Europe Core. How can this be explained?

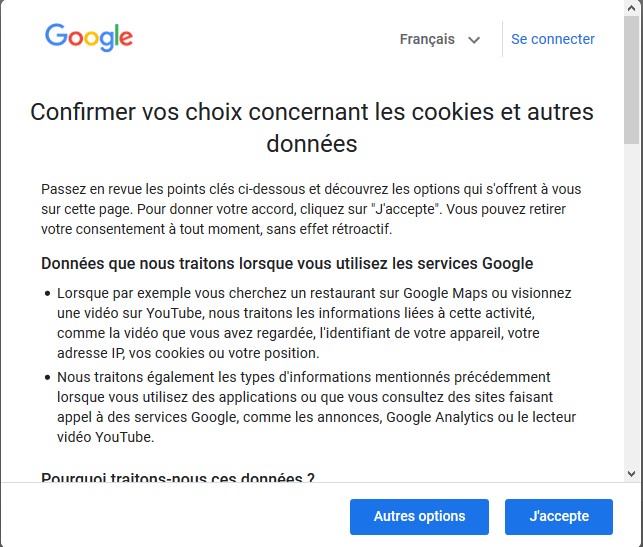

The sanctions in question concern the compliance of these companies’ practices in terms of “cookies” placed on the terminals of Internet users. However, this issue is mainly covered by a specific directive on electronic communications, known as “e-privacy”.

Excerpt from the cookies banner of google.fr, captured on January 27, 2021.

The e-privacy directive does not include, explicitly at least, any one-stop-shop mechanism.

However, e-privacy, a special text (to electronic communications), regularly makes references to the general data protection text (i.e. the GDPR).

A fierce battle has been waged by lawyers for Google and Amazon to demonstrate that the one-stop-shop of the GDPR should be “imported” into e-privacy. The details of this argument are not discussed in this outreach bill. Let us retain the most powerful argument of the CNIL, the one that wins the conviction. The control of e-privacy can be entrusted, at the free choice of each Member State, either to their data protection authority (their CNIL) or to their telecommunications regulatory authority (their ARCEP).

However, the one-stop-shop of the GDPR, as we have seen, calls in its operation a meeting of all European CNILs called EDPB. The European ARCEPs do not sit on it. The conclusion is that there is a logical impossibility to make the one-stop-shop work in terms of cookies. The CNIL therefore considers itself competent with regard to cookies deposited on the terminals of users residing in France.

Who’s next ?

The CNIL having found its hammer, it strikes, and strikes hard, twice as hard as in the Android case. The message seems clear: if it cannot use the GDPR, it will use the e-privacy directive as a new weapon.

Under these conditions, we see no obstacle to the French authority attacking players that have always escaped it until now, first and foremost Facebook.

One can certainly criticize the cookie practices of Google or Amazon, and we refer for detailed comments on this point to our commentary to be published in Dalloz IP/IT: “E-privacy or the continuation of the war against targeted advertising by other means”.

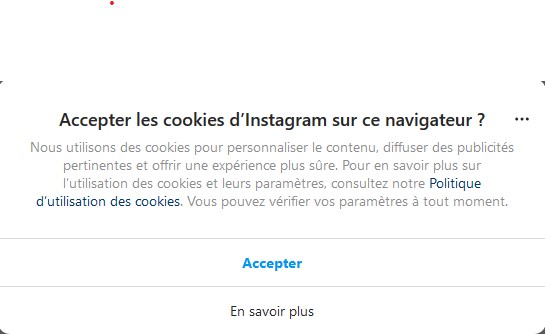

But to say that the Facebook group’s practices in this regard are no better is an understatement. Instagram’s cookie banner first looks like this:

Excerpt from Instagram’s cookie banner, captured on January 21, 2021.

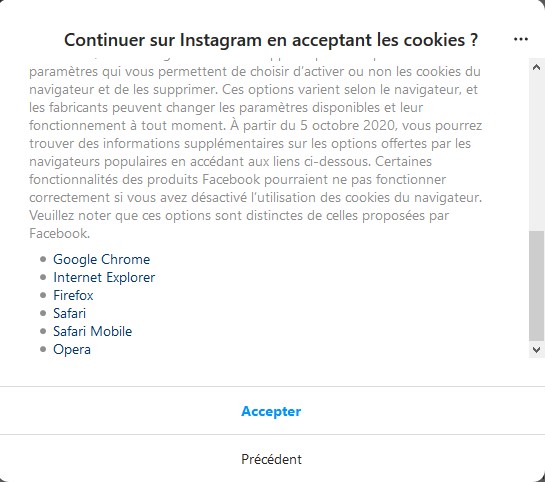

But a click on “Learn more” will take you there:

Extract from the Instagram cookies banner, captured on January 21, 2021.

Still no button to refuse non essential cookies. A “back” button that allows you to go back to the first banner and start an endless loop. A text that invites you, if you really want to refuse cookies, to do so via your browser settings – kindly offering you a link to the appropriate documentation! It is hard to see why the CNIL, once emancipated from the one-stop-shop chains, would deprive itself of seeing these elements by a simple online check.

The real challenge: the future of targeted online advertising

Finally, we must warn against a simplistic and Manichean approach to the issue, which would turn all these Californian companies into evil entities driven solely by the desire to harm users. In a previous publication (still under a publisher’s embargo), we tried to explain that it was absurd to refer the huge question of the “free service versus targeted advertising” business model to supposed individual arbitrations via checkboxes, when it is a question to be settled politically and collectively. We will come back to this issue in a month’s time, when we will publish an article specifically dedicated to it in Storck Mixes. A popularized summary will be proposed here.